Anyone who’s buying multifamily real estate, in the 'deep water' where the 'big fish' swim, will likely have some experience with how to obtain financing. Most will seek out some debt and equity combination: usually, a traditional bank loan for the former and personal cash savings for the latter.

When transactions have double and triple-digit unit counts, it’s easy to understand why some like ‘sticks’ and that there are situations in which a bank loan and personal savings are not sufficient to finance a purchase. In cases like these, preferred equity and mezzanine debt can be useful alternative sources of capital for obtaining a multifamily property.

What is Mezzanine Debt?

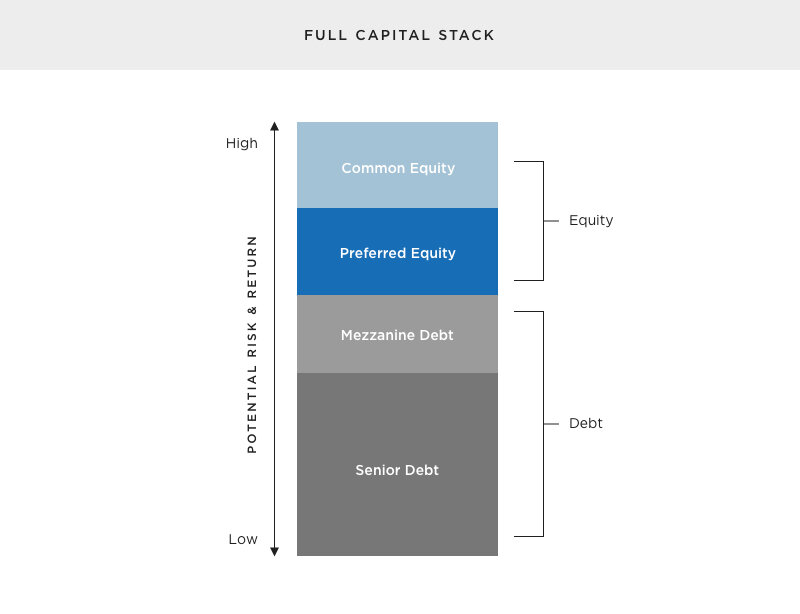

In commercial real estate, conventional bank financing is generally considered as an initial source of capital. The bank maintains the first mortgage position, and as such, that loan descends the capital stack. Most borrowers will solicit the bank for upwards of a 75% loan-to-value (LTV) ratio for their deals, which some may not secure for various factors. This is the space whereby mezzanine debt can become a viable option.

Mezzanine debt is a bank or private capital loan that is subordinate to senior debt financing. It maintains the second spot in the capital stack, like other recorded debt but above all equity positions. The mezzanine debt deals can often be two or three times as expensive as traditional bank debt, but no principal amortization is expected.

What is Preferred Equity?

Preferred equity is a funding angle that has been around forever but has only recently arisen in the commercial real estate world. Preferred equity is equivalent to preferred stock in the corporate finance world. Preferred equity is secondary to all debt but higher to all common equity. Therefore, preferred equity is typically thought to hold roughly the third position in a commercial real estate capital stack.

It usually is employed in three situations:

A mezzanine loan already exists, but the borrower lacks additional equity to complete the project.

The senior debt providers underwriting does not recognize a mezzanine loan.

The borrower is seeking to decrease leverage and improve liquidity.

Preferred Equity vs. Mezzanine Debt

Although mezzanine debt and preferred equity serve in similar capacities and the cost of capital is around the same range, there is a crucial difference between the two: as their names suggest, one is equity and the other is debt.

Because mezzanine financing is regarded as a loan, they are recognized as lenders. Mezzanine debt providers have specific and limited “self-help” remedies under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) that permit a secured lender to pursue remedies against its collateral without the need for and cost (and delay) involved in judicial action like foreclosure. These solutions are subject to UCC requirements that often override contrary provisions in the mezzanine loan documents. A stark contrast to equity holders.

In terms of the cost of money, mezzanine debt and preferred equity are approximately the same. Mezzanine debt is a hybrid form of capital that is part loan and part investment. It is the highest-risk form of debt, but it offers some of the greatest returns. A typical rate is in the range of 12% to 20% per year.

An existing building might be valued around 8-12%, whereas given its higher risk profile of a project coming out of the dirt, a construction deal might be in the price range of 10-13%.

Preferred equity is priced somewhat higher, usually around 1% more than what one might expect to get with mezzanine debt. Real estate preferred equity investments can generate anywhere from 8% to 15% returns but offer a protected position that lowers risk and regular income that equals or can exceed the expected profits we’re seeing from common equity today. The points accessed by either the mezzanine or preferred equity can offset any of these differences in rates depending on how the deal is structured.

An added difference among mezzanine debt and preferred equity is linked to how cash flow is distributed. For instance, if both pay a 15% interest rate. Typically, a mezzanine lender will expect a 9% payment and accrual of 6% with no cash distributed until the sponsor meets the minimum 9% threshold. Private equity investors are more inclined to close on a deal in which the entire 15% must be paid in advance of any cash distributed to the sponsor or common equity investors.

Restrictions on Senior Debt

Mezzanine debtors use different criteria than banks in qualifying borrowers. Common senior debt lenders include credit companies, commercial banks, and some insurance companies. They lend those funds based on the asset’s value, and as before-mentioned, it uses that investment as collateral for getting the loan.

Oppositely, mezzanine debt is not collateralized by assets. As a substitute, mezzanine rates look at EBITDA, their EBITDA margins, and the strength of their historical cash flow, in essence, are against the cash flow of an asset/investment or business. Mezzanine lenders usually aim for an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 15% to 20%.

The biggest impediment for sponsors to overcome when seeking mezzanine debt is their senior lender’s approval. An inter-creditor agreement is negotiated between the senior lender and mezzanine lender, and that arrangement describes the mezzanine lender’s rights and cures in the event of default. The senior lender ordinarily has the upper hand in these dealings and will generally forbid a range of cures to protect its position.

Preferred debt is at the bottom concerning recovery, and the senior debt provider may require that specific conditions be met. For example, the lender might want any equity transfer above a specified threshold to be subject to a customary “know-your-client” review. The bank may require any transferee to satisfy particular net worth and liquidity requirements. The senior debt provider may even need the original preferred equity investor to maintain a specific investment percentage ownership. In the event of non-payment, the preferred equity investor might vacate the developer as a manager and the preferred equity investor may be forced to submit quarterly reports that provide comprehensive financial statements.

Weighing the facts between the Debt and Equity

When buying multifamily real estate, there are unquestionable benefits to utilizing either mezzanine debt or preferred equity. Mezzanine debt will likely interest anyone struggling to raise equity; it allows the buyer to bridge the space between the senior lender and common equity. The most significant comedown to mezzanine financing is that it’s still leverage. Advanced borrowers are usually careful about becoming over-levered.

Preferred equity offers an increasingly viable alternative. Most lenders want at least 15% of capital in a deal to be equity. Very few banks will accept mezzanine financing as equity; conversely, most will accept preferred equity as an equivalent. Preferred equity is also an attractive way for buyers to improve their liquidity (instead of selling an asset) or grow their portfolios. This also enables sponsors to preserve all upside after agreeing to a preferred return.

These considerations notwithstanding, the nature of the deal – including the conditions imposed by the senior lender – will principally dictate which of these financing tools is most appropriate. Like all savvy shoppers around, talk with many different bankers to distinguish which products are best for you or your group.

Capital Stack — Position and Financing Subordination